A new architecture for a new kind of human beings

Fashion has always been a phenomenon that interprets and reflects the society of which it is an expression, telling dreams and visions and interpreting technological, scientific and cultural discoveries.

The event that has had the greatest impact on society in recent years is the pandemic. Our daily lives have changed, but our way of perceiving ourselves and our relationship with technology and the world has changed even more. We have realised how our destinies as individuals are intertwined, how our survival is linked to that of others and to the health of the environment. And in this period of profound uncertainty, our gaze has turned both to science, asking medicine and chemistry to find a cure for the physical ailment that was afflicting us, and to new technologies, asking them to provide us with the means to fulfil our daily and professional needs to connect, interact and exchange ideas, emotions and even material goods at a distance. We realised how real and important the virtual dimension really is and how it is inherent in our very nature.

These reflections arise from the extraordinary opportunity I had to talk with Philip Beesley - architect, visual artist and director of >>>Living Architecture Systems Group in Waterloo, Canada – and Sascha Hastings – very skillful curator and art producer and nice person – about Philip’s work presented at the 2021 Biennale Architettura.

This opportunity arose from a series of fortunate coincidences. I had the opportunity to meet (virtually) Philip a few years ago, on the occasion of an interview I conducted for a magazine I was working with at the time, and I immediately appreciated his artistic work and his great empathy on a personal level. Afterwards, I was able to meet Sascha, the very skillful curator who followed the organisation of the transfer of his work from Canada to Venice: the last chat I had in front of a cup of raku ceramic tea in Venice before the lock down in 2020.

From there I followed the fate of the Grove installation until finally, this year, I was able to admire it in all its beauty at the Arsenale in Venice.

This resulted in two interviews that I propose in two very exciting articles! You can find one below as you continue reading, the other one at >>> this link!

Interview with Philip Beesley

How can we live together?

Maddalena Mometti: How did the concept for Grove installation come to your mind? What inspired you?

Philip Beesley: What inspired me at the very beginning of this project was the question that Hashim Sarkis sent to me in his very first invitation at La Biennale di Venezia: “How will we live together?” It made me pause and try to gather hopes and dreams in response.

In answering that question I made a little drawing. The drawing shows a rather strained surface of the earth. I have been fortunate in living on strong, solid land. In Canada, I can sometimes stand on intensely deep, solid granite, carved by the ice ages. Similarly when I lived in Rome, I loved standing on the tufa rock, with its deep, soft surfaces hardened by the sun. Yet the land that we now stand upon seems very different from those confident examples.

In this drawing I wanted to express the feeling that the earth is insecure. The surface seems almost hollow, trembling. That feeling was the start of the Grove project. Living on that surface I asked the questions: “If we will live together, who are we? Are there many kinds of beings that can live together with us?”. My little sketch drew groups of different beings: some old, some young, some able bodies, some less able. It includes small and large, and fragile individuals alongside proud leaders. The drawing shows groups of beings asking the question: “Can we live together?” This kind of gathering is both hesitant and strong at the same time: hesitant because this group do not come from one nation or one family or one company, and also strong, because the gathering of multiple different kinds of species and humanities seem intense and fertile.

In my drawing, reaching far overhead, above this trembling ground and the gathering of people, there is a radiant lace-work of clouds, creating canopies, and shells, and nests, and webs. This offers a kind of gentle architecture. It offers a common song of hope.

That was the sketch of what we hoped we would be able to offer in the installation. The work was titled Grove, like the opening in a wild forest, where we could gather in peace, a foundation place of a city. This might remind us of legendary beginnings of historical cities. Perhaps this ‘grove’ might even feel like a temple, opening us to powers that lie far beyond us. Whether large or small, this architecture acts as the most gentle gathering place.

We live in urgent times. We need so much hope!

The gentle architecture after the pandemic

Maddalena Mometti: How has the current international situation of the last two years and the related constraints affected the creative process?

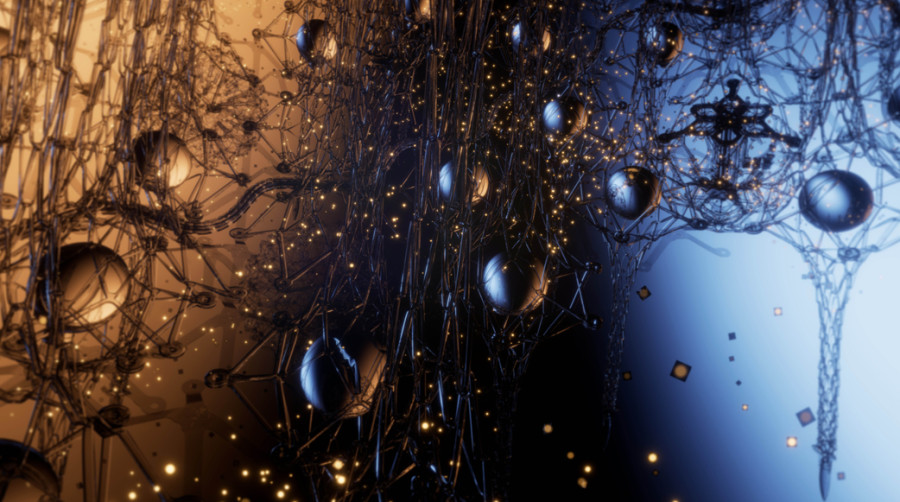

Philip Beesley: At the beginning, before the pandemic, the project was based on a deeply physical gathering place. We conceived a radiant spring opening inside a forest, evoking original growth where the first city gathers. A full range of mechanisms and architectural components were developed to build that vision. We tried to consider dimensions far behind human domains enriched with living beings of all kinds and the emergence of life, and minerals and elemental material as well. We were thinking about whispering songs and distributing sounds and gentle movements: the experience of a new kind of artificial life interweaving with natural life. New flexible skeleton scaffolds, basket-like columns and shells, and new meshworks of microprocessors were all prototyped and launched toward mass manufacturing. We started working very hard, more than two years ago , building up this physical paradise- garden.

And then everything changed with the pandemic. For a while we thought it would be impossible to recover. We were forced to close down. Like so many others, we said: “We are so sorry, it is impossible!” But Hashim Sarkis and his group encouraged us to renew things and to find a way to continue. So, we tried to change. Instead of a completely physical work, we thought about a layered and open system, not depending so much on epic scales and major resources. We conceived a lace-like open cloud that could spread and nourish while at the same time consuming only the lightest, most minimal resources. We imagined offering an architecture transformed into a gentle air filled instrument, full of light and shadow and sound. That led us to conceive of making a film, translating as much as possible from the physical design that we had intended to build and recreating it within a virtual world.

The film: a dialogue between Architecture, Design & Fashion!

Maddalena Mometti: This is the first time you translate your work into a film… is it correct? Tell us your experience, please!

Philip Beesley: Yes, this is our first major work in film. With the renewed vision of working with these immaterial, energy-filled dimensions, we reached out to four collaborators– the brilliant film-makers Warren du Preez and Nick Thornton-Jones, the sound-composer Salvador Breed, and couture artist Iris van Herpen. With Warren and Nick, we took the deeply interwoven component patterns that had been intended for physical fabrication, and we translated those into projected digital animations, rigged and animated within comprehensive virtual world. With Salvador, we conceived of vast fields of sound, using multitudes of individual small speakers that could carry intimate whispers while also growing into thundering storms. Conversations with Iris revolved around the emergence of a child-like being who might live within interwoven membranes floating within the space of Grove.

Combining all of those conversations, we created the film together. We worked on some new softwares that allowed us to translate the massed arrays of intricate architectural components into animated fabrics that shift and flex, and that could carry transparent liquids and crystalline light. We engineered a new kind of speaker that could radiate sound all around it, and tuned it so that it could carry a wide spectrum of frequencies. We designed a floor surface with a hollow that could receive the projected film, giving the experience of looking into a deep pool carved into the ground.

As soon as the film started to emerge, we discovered just how potent that new medium could be for us. It allowed us to go further in emotional dimensions than we’ve every gone before. It seemed to allow us to touch joy, all the while building up new crystalline worlds. We traced the story of a child in birth. That in turn allowed us to embrace suffering as well, and eventually we also embraced almost unspeakable loss. All of those dimensions can, I think, be seen within the film.

It impressed me very much how closely architecture and industrial design and the world of film and fashion too can come together. A kind of new possibility-space where forms and visual gestures, sound and video all work together.

Maddalena Mometti: And it is a good metaphor of our times! Above all in these two years we perceived that digital is very physical for us in some way! During the lockdown period digital meetings were the only contact with other people! And we really needed this kind of relationship!

Philip Beesley: That makes me think of a realization that comes from the reality of the last couple of years in which on one hand we can say that everything is virtual, the weaving of all the possibilities is projected onto the potential of virtual media, a complete world. On the other hand those digital forms are of course profoundly physical. I love the sense that these things are in fact one. It is a false opposition. Ideas are actions. Actions are ideas. In Nature opposite dimensions constantly arise together.

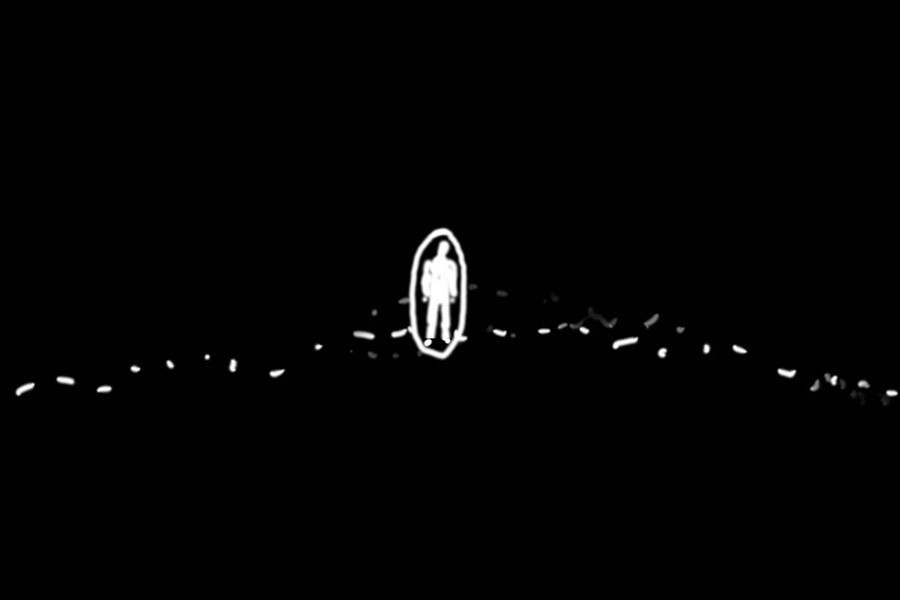

Maddalena Mometti: Let’s talk about the film in detail! It was very surprising to me and very captivating! In some moments I had the impression of being a spectator, in others I had the feeling of being the human protagonist myself and thus having a subjective view…

Philip Beesley: Yes, the vision inside this film does invite you to feel like you are inside it, and even that you are dreaming of the world that you are seeing. In the first part of the film you can see emptiness and distance, then slowly you get closer and more deeply involved. You might feel that you are breathing and evolving. There is a sense of being embraced. Then, suddenly, you are flung back into a terribly alienating space, as if an unthinkably large explosion has happened and you are left with the terrible aftermath. Small flickers of motion arise again, and slowly build, and you find yourself deeply immersed again. Those cycles continue, with increasing intensity. When I watch the film I find it both very encouraging and also frightening and disorienting.

I am encouraged by the possibility of offering people an experience that can be glacially slow and also sharing an intense energy. Salvador has woven together a tissue of sounds that accompany this immersive world.Some of the sounds are alien and artificial, utterly cold. In some other parts of the film the atmosphere is welcoming, and joyful.

A new kind of human being?

Maddalena Mometti: In the film is there a sort of projection of a new kind of human being?

Philip Beesley: Yes. The film attempts to create a kind of new myth of the origins of life. Within that new myth, a new child is offered. Perhaps this child is a new kind of human being with the body of a cyborg whose body contains densely interwoven artificial and natural parts, living intertwined within both nature and technology. The film builds on that vision. For parts of the film, a child can be seen, within the space of a nest, deep within layered meshworks. Within those parts, the sculptural forms seem fertile, like nests surrounded by lush soil. We can see the child stirring, gently touching and reaching.

The sound that accompanies this film includes spoken texts from the nineteenth-century French author Gustave Flaubert’s Temptations of Saint Anthony. That author inspired a generation of surrealist artists who followed him, and I have returned to him again and again for inspiration within my own work. The Temptations evoke tribulations that overwhelm the Saint in tumbling nightmares. It then moves into lovely passages where the Saint feels united with rocks, minerals and plants. That metamorphosis is a gift of life from death. For me, the child within the film embodies that transition. That’s what we want to offer with Grove in this intensely strained time: a gift of life from death.

Let me say a little more about some fundamental ideas within this project. Some old myths suggest that life is always separated from technology. Within that way of looking at the world, the myriad forms of non-human living plants and organisms somehow carry tangled disorganization and disease, while the inert minerals and pure elements might seem like better and stronger building materials that allow us to control and clear the world, making it safe. Lifeless minerals might be for tools and for making the walls and floors of architecture, with nature kept safely outside and under control. I think this idea is present in many parts of our culture. I think that separation has created deeply harmful conditions in the world.

However, I don’t believe that separation is necessary. I love the sense that we could look very carefully and slowly at a rock and ask, in all seriousness: ”Is it alive?” In some remote parts of our culture, the answer could be ‘yes’. The ancient Greek principle of hylozoism suggested that. Hylozoism means ‘life from material’. That concept is one of the bases for the construction of the film- the sense that it is not necessary to have a strong separation between you and a rock or a tool.

I tried to express that idea by presenting primary elements, organized in harmonic arrays. Waves of energy transform them into new kinds of material. They make chains and bundles. Metabolic reactions rise up and transform them again. The crystalline structures of those forms attract new materials and organize them, acting like templates. Information emerges, coded within their structures, carrying the patterns for composing those bundles and groups. Chains and membranes roll and curl, making rippled surfaces. They react and exchange. Hollows emerge, and curl in on themselves. Curling membranes connect into vessels and nests. There are waves that ripple out ahead and backward from those actions, creating kinds of projection and memory. Perhaps even consciousness emerges within those ripples of reaction.

Within the thickets of sculpture that surrounds the child’s body, resplendent life flows out, budding and swelling with innumerable plant and flower-like forms. Clouds roll far above, suggesting that this landscape might continue into multiple worlds. Within other parts of the film, we witness a desert-like plain that takes over the landscape. Shattered forms speak of intense forces that have swept over the land, obliterating almost all living forms. The child also appears momentarily within those sections. We witness them buried, in death, in a vision of sacrifice where they might be transforming into soil. Those transitions continue with life succeeding death and subsiding again in multiple cycles.

This is a potentially valuable message, I think. We are not alone. Our actions ripple out and touch everything. Everything around us touches us. The story of the film is based on that.

The physical installation

Maddalena Mometti: What about the materials of installation?

Philip Beesley: I hope the qualities I’ve been describing might also be seen in some of the physical craft of making Grove. I think you can see that at work in the canopy, made with lightweight and resilient polymer sheets. That can also be seen in the thicket of standing speakers that surround the viewer, with each printed shell floating in a delicate basket of stretched metal. Those forms attempt to be sensitive, offering intimacy.

The main fabric that we can see in Grove is a large suspended fabric made from PETG polymers, while the speaker shells seen within the standing columns are printed from synthetic material, made from a bioplastic based on plant sugar. The fabric is cut using a laser, using carefully-developed patterns that attempt to form reactive frond-like forms that can be stirred into action with only the slightest of touches.

Maddalena Mometti: Did you create these polymers (above all the bioplastic) especially for Grove or did you already work before with them?

Philip Beesley: Some materials are traditional, some of them are new. Polyactic Acid (PLA) printing filaments have now entered wide use, thankfully. We are trying to improve the materials we use. We are still searching for a bioplastic sheet that can be flexible enough to handle wide twisting and bending forces while also staying transparent. We aren’t close enough to that goal, but it seems that progress is being made. For now, we are continuing to use recyclable PETG polymer sheet, while we search for replacements that come closer to fully circular design standards where all material can be reused, with minimum carbon impact in the world. One of ways we have made strong progress is in using a radical minimum amount of material by using very thin sheets.

We work with compliant force-shedding design. We try not to resist forces. Instead, we are working to create something as flexible and resilient as possible. This way, the systems can handle wide environmental changes. When I was learning architecture I was taught to build things in the opposite way, following the Roman writer Vitruvius’s philosophy of making strong things, built to last: “First of all firmitas!” My new work, however, tends to oppose that view. I do not believe we need more walls today. I believe that as architects we need to conceive open, deliberately flexible and ephemeral systems.

Maddalena Mometti: How about the name Grove?

Philip Beesley: I love the word grove, because it means a place of presence and a place of opening in a kind of wildness, embracing the surrounding space. The idea of a grove is a fundamental gathering place. It offers an opening, a fundamental emplacement. This is not an act where we claim territory. The opening invites gathering, and speaks of the deep tradition of democracy.

I think a new space for democracy needs new kinds of space. To me, it is motivating to hear the voices of new physicists encouraging us to consider new conceptions: rather than describing space fundamentally empty, with individual atoms dancing like infinitesimally small spheres, surrounded by void, I think I am now encouraged to see a possibility of mass arising everywhere. In the quantum realities that are now being confirmed by the amazing experiments of the CERN instruments, it even the birth of mass itself could be seen as a kind of fundamental particle, the Higgs boson. If mass can arise everywhere, then space is full, not empty. Encouraged by this, I am tending to use new terms as well. I think we could use the mediaeval word aether instead of the rather cold and somehow polarizing word space. I love the sheer fertility and potent fullness that aether evokes. Grove embodies that kind of gathering space.

The mechanical empathy

of responsive buildings

Maddalena Mometti: I read the press release: your installation was described using the word empathy. How can this kind of empathy be put into architecture projects of real buildings and cities?

Philip Beesley: I am optimistic about the possibility of responsive buildings offering a precise kind of mechanical empathy that might help renew what architecture can be. Empathy can be felt when a person sees that their own thoughts and feelings are being fundamentally ‘heard’ and integrated by others. Empathy could also be expressed by mechanisms and buildings, where those systems sense what humans are expressing and respond to those expressions. Perhaps some examples of that are now ordinary: we take for granted that a shopping-mall door will open before us when we walk toward it. That ordinary example might suggest that mechanical empathy is a viable technical craft, but I should acknowledge that it is also full of problems. It can also imply that we are not free. An active mechanism can even become a monster that can hurt us. So, the power of this way of working is large. However, if we look more closely at scaffolds and information together, it seems possible to make architectural fabrics that are very senstive in their mechanisms. Rather than simply pushing and pulling, manipulating things with maximum power, they can resonate and harmonize the forces that pass through. With computational controls, we can orchestrate ‘learning’ functions that help the work to act sensitively. So this kind of work becomes empathic, hearing what you say, moving with you, anticipating what you are going to do and in some way shifting and dancing with you. We need to work to make building sensitive, learning from human empathy.

Maddalena Mometti:A beautiful vision!

About Venice

Maddalena Mometti:My last question: which is your personal relationship with the city of Venice? Is there a connection between this city and Grove?

Philip Beesley: Grove is conceived to work precisely with the Arsenale, casting shadows and echoing within that extraordinary and vast space. Its canopy projects clouds that float in the imagination out amidst the canals and walkways of Venice. The ground of Venice has so many kind of histories into it. By spending extended time on that ground my body becomes touched by a certain way of walking and being. The floating city is of course a place of dream, a place that concentrates urban space, ground, water. The sun rises and sets on the great lagoon. The water is moving all around you. This experience of moving up and down against a surface of water, in and out, produces the most delicious sense of immersion. In that space it is possible to experience qualities of amphibian beings. It is the space of dreams for me. The most vivid dreams happen when I sleep in Venice. Its haunted sounds and whispering echoes are eternal. Venice is irreplaceable.

>>> Go to the interview with Sascha Hastings!

Other posts on new fashion scenarios:

>>> The journey of a work of art from Toronto to Venice Interview with Sascha Hastings

>>> Fashion is design Il ritorno della Moda con la “M” maiuscola a Venezia

>>> Digital Glamour: when fashion opens up new worlds “Digital as the fifth element, in addition to air, water, earth and fire” by Chic Words

>>> Green Carpet Fashion Awards 2020 “What we wear speaks to who we are and what be believe in” Robert Downey

IMAGES

All photos are courtesy of Philip beesley and Sascha Hastings.

Starting from the top:

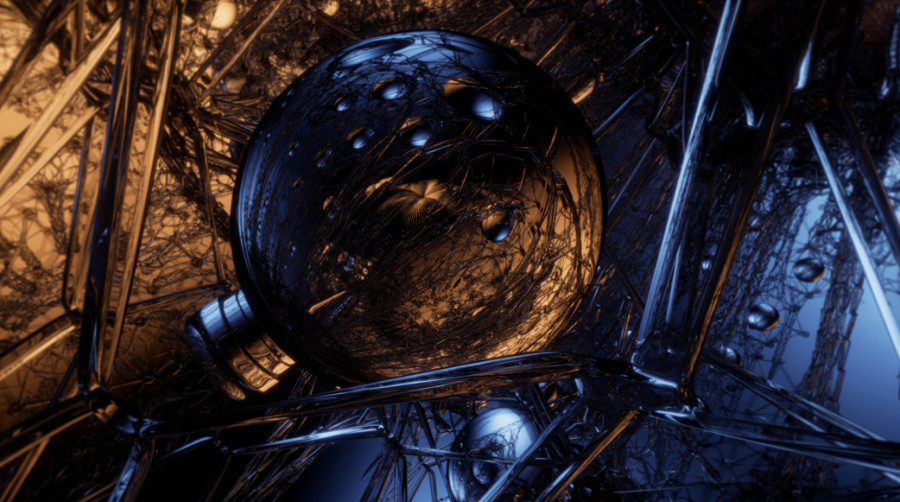

[image 1] Screenshot of Grove Cradle film

[images 2,3,4] Preparatory sketches for the Grove installation by Philip Beesley

[images 5,6,7,8,9] Screenshot of Grove Cradle film

[images 10,11,12] Grove installation photos

[immagine 13] Chic Words visiting the Grove installation